The outbreak of H1N1 influenza in India this year, which has

killed 875 people since 1 January, is not yet a major concern

because the incidence and mortality are no different from those

caused by seasonal flu in developed countriessuch asthe United

States, infectious disease specialists have told The BMJ.

However, they said the Indian government should now

recommend vaccination for at-risk groups including elderly

people, patients with chronic diseases, pregnant women, and

young children.

India does not currently recommend yearly influenza

vaccinationsfor the general public because the burden of H1N1

is so small when compared with diseases such as tuberculosis,

which affected 2.1 million people in 2013.1 Such a vaccination

becomes ineffective after a year and takes 3-4 weeks to confer

immunity—making its large scale use impractical, said Jagat

Prakash Nadda, India’s health minister, in written responses to

questions raised in the upper and lower houses of the Indian

parliament this week. However,since the H1N1 outbreak began

last year the health ministry has recommended a vaccine for

public health workers who come into contact with infectious

patients.

The H1N1 epidemic has affected 15 413 people since the start

of 2015, compared with 27 236 in 2009 and 20 604 in 2010.

The death tolls in 2009 and 2010 were 981 and 1763,

respectively. This year the most affected state has been

Rajasthan, with 4734 confirmed cases, followed by Gujarat,

with 3337 cases.

Rising mortality has led to panic among the public and an

increased demand for diagnostic tests and treatment, even among

people with no flu symptoms. This has put extra pressure on

the limited infrastructure available for swine flu testing in India.

Currently, only 46 government laboratories across the country

can test for swine flu, in addition to accredited private labs. And

demand for more tests has led to overcharging by private labs,

some of which have charged Rs 3000 to Rs 9000 (£31 to £94;

€43 to €128; $49 to $146) for a test.

The Indian government’s response has been to ask the drug

controller to ensure the availability of the antiviral drug

oseltamivir (Tamiflu) in all stores that have a licence to stock

it, as well as regulating prices of swine flu diagnostic tests,

which have risen since the outbreak began. The worst affected

states,such as Gujarat, have taken stronger measures: yesterday

the Gujarat government banned public gatherings from taking

place without permission, in an attempt to stem the spread of

the disease.

The strain of H1N1 circulating this year is the same as that in

2009, the health ministry said. George M Varghese, professor

of medicine and infectious diseases at the Christian Medical

College in Vellore, Tamil Nadu, said that the resurgence of the

disease could be because people who acquired immunity in the

2009 epidemic have now lost the antibodies, making this a

natural spike in the disease cycle. Nevertheless, the epidemic

is expected to die down in a month or two as temperatures rise

and conditions become unfavourable for the virus to transmit

itself, doctors told The BMJ.

While the mortality rate of 5.6% (875 of 15 413 cases) seems

high and has raised concern among the general public, it does

not indicate the virulence of the disease, said the doctors: the

actual number of affected people is likely to be far higher than

15 413 because only severe cases and deaths are reported. The

mortality rate from H1N1 istherefore probably lower than 0.5%

and closer to the mortality from seasonal flu in developed

countries such as the US.

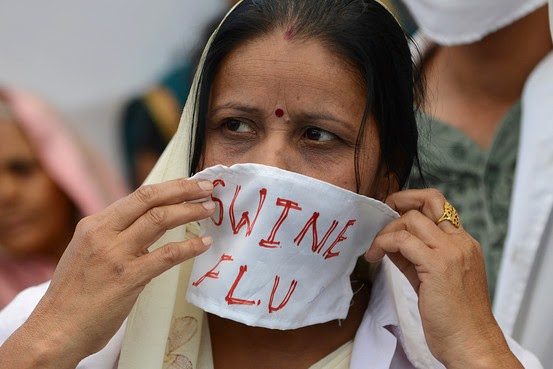

H1N1 tends to cause complications only in people with

pre-existing conditions. Dilip Mathai, dean of the Apollo

Institute of Medical Sciences and Research in Hyderabad, said

that vulnerable groups of people, such as pregnant women,

elderly people, and public healthcare workers, should therefore

use facial masks and be vaccinated.

Most doctors The BMJ spoke to said that the government’s

response to the current epidemic was adequate, but a few experts

argued that India is lagging behind in epidemiological and

genomic research into H1N1 outbreaks, which is critical in

anticipating future epidemics and vaccines’ effectiveness.

Thekkekara Jacob John, clinical virologist and formerly a

professor at the Christian Medical College, said that India was

not tracking the prevailing strains of flu or the climatic and

social conditions that can trigger an outbreak. The lack of a

public health ministry in India, he said, means that India is

missing out on valuable early stage data during an epidemic,

which can curtail its spread.

He said, “A public health department would have kept track of

which virus is beginning to show up as seasonal flu. If it was

H1N1, an immediate response should have been instituted a

few months ago.”

Another gap in India’s response has been the lack of data on

the swine flu viral genome. India has contributed surprisingly little to global databases on the influenza genome even though

it sees frequent large outbreaks, said Ram Sasisekharan,

professor of biological engineering at the MassachusettsInstitute

of Technology, USA. This means that India may be unaware

of mutations happening in different regions of the country, he

said, which may render vaccines ineffective against the disease.

_0226_-_Swine_flu.jpg)